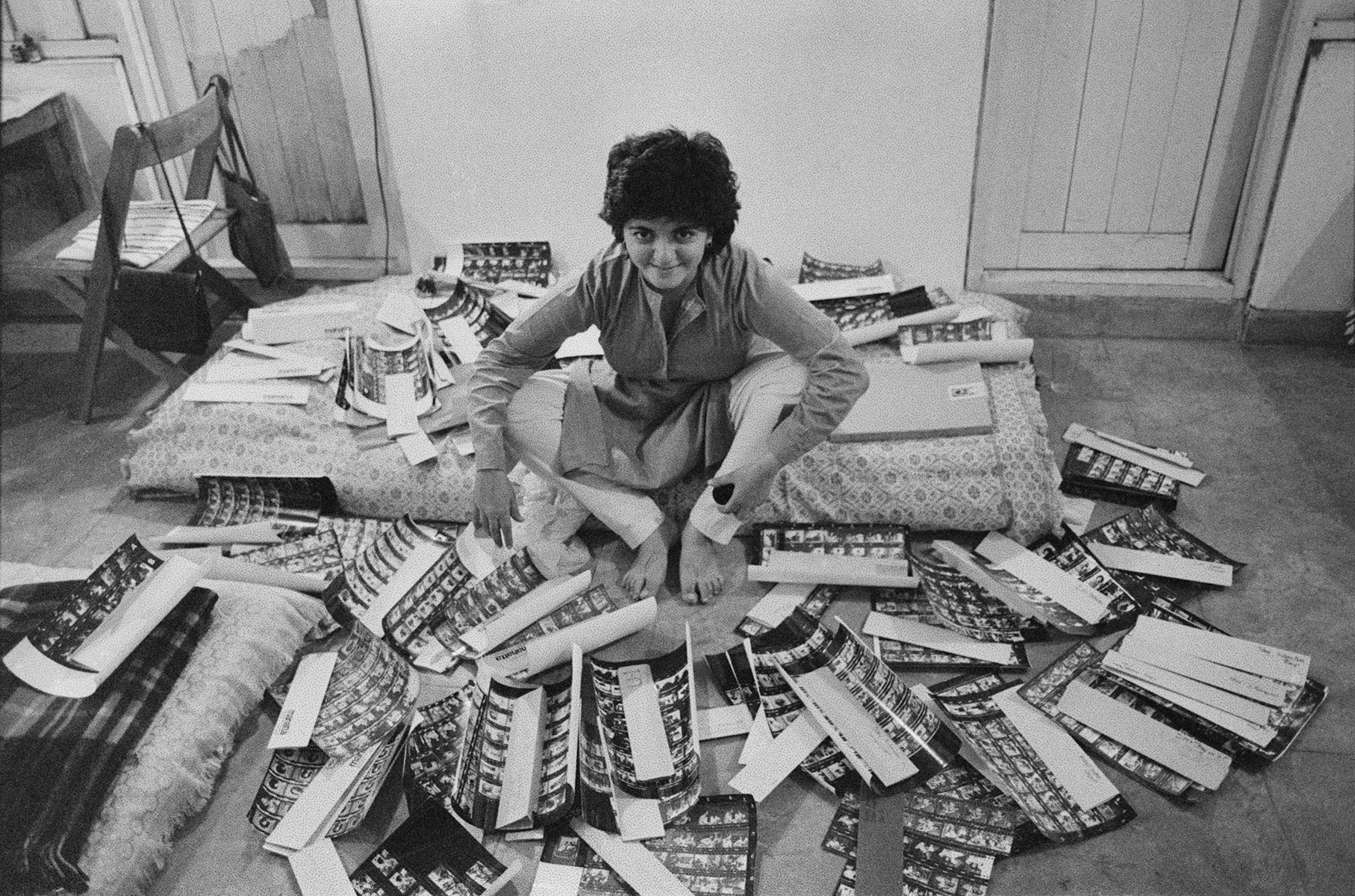

Dayanita Singh, Let’s See, 2021 Photo: Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh, Let’s See, 2021 Photo: Dayanita Singh

You’ve just opened a career survey called Dancing With My Camera. What can visitors expect from the show?

Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter

NEWSLETTER

Leave this field empty if you’re human:

They will get a wonderful surprise when they see there are hardly any photographs on the walls. This will be the first time I show what I’ve been wanting to do for the last 15 years – which is to take the prints off the wall and put them in these structures. I want people to experience the image rather than just see it.

By ‘structures’ you mean your Mobile Museums, wooden cabinets that allow the images inside them to be constantly edited, archived, re-ordered and altered. These have created a completely new way to exhibit photographs…

Exactly. I am tired of people looking at photographs with one sweep of the eyes: I want them to experience the work with their body, to walk around the work and not ever be able to see it in one gaze. In the Mobile Museums, you have to get down and move around. So I hope this makes people think about how we can shift ways of experiencing the image. The Museums also force visitors to take a curatorial role. In Berlin, I am going to ask some of the curators to install the Museums, to put the images in, and they are going to invite different people to come in and re-curate the Museums and reactivate them – I don’t want my work to be fossilised behind glass. I want it to be alive. That’s why ‘Museum of Chance’ took me two years to make: I had to make sure it worked in every combination.

I think there is another kind of gallery waiting to be made, a space in between the publishing house and the big fine art gallery.

Speaking of ‘Museum of Chance’: is it true that when the Museum of Modern Art in New York called you about purchasing that work, you thought it was a prank?

Completely. I didn’t believe it. Then I went to MOMA, and I was in an elevator, and I was surprised to see a trolley with my name on it. I asked about it and somebody said the museum director, Glenn Lowry, was giving a talk on my work. So of course I went along, and I just cried, because he was saying that the ‘Museum of Chance’ is how he would like the new MOMA to be – that it is his favorite work of art in the entire collection. He, of all people, understood my critique of the museum. And he wanted his museum to be organic and ever-changing, just like the ‘Museum of Chance’.

One of your breakout works was the book Myself Mona Ahmed, which is about your relationship with Mona, a Eunuch who lived in a graveyard until she passed away in 2017. Your closeness really comes through in the exhibition.

Absolutely, Mona was my mother, my child, my sister. And on the street she was like a true man friend – if someone looked at me or whistled, she would hurl the filthiest abuse at them. Then we would go back to her house, and we would lie together and talk about sex and boys and lust and things you wouldn’t talk to anyone else about. She never got shocked by anything, there was no judgement with Mona. She was an exceptional person, a complete outsider. In the graveyard where she lived, she built a swimming pool, because she had the idea she could teach Muslim women how to swim and that would be very liberating for them. Later she suggested we turn it into a pickle factory and call it Ahmed Pickles. She believed, that because I worked as a photographer for the London Times, we could sell the pickles in London and advertise there.

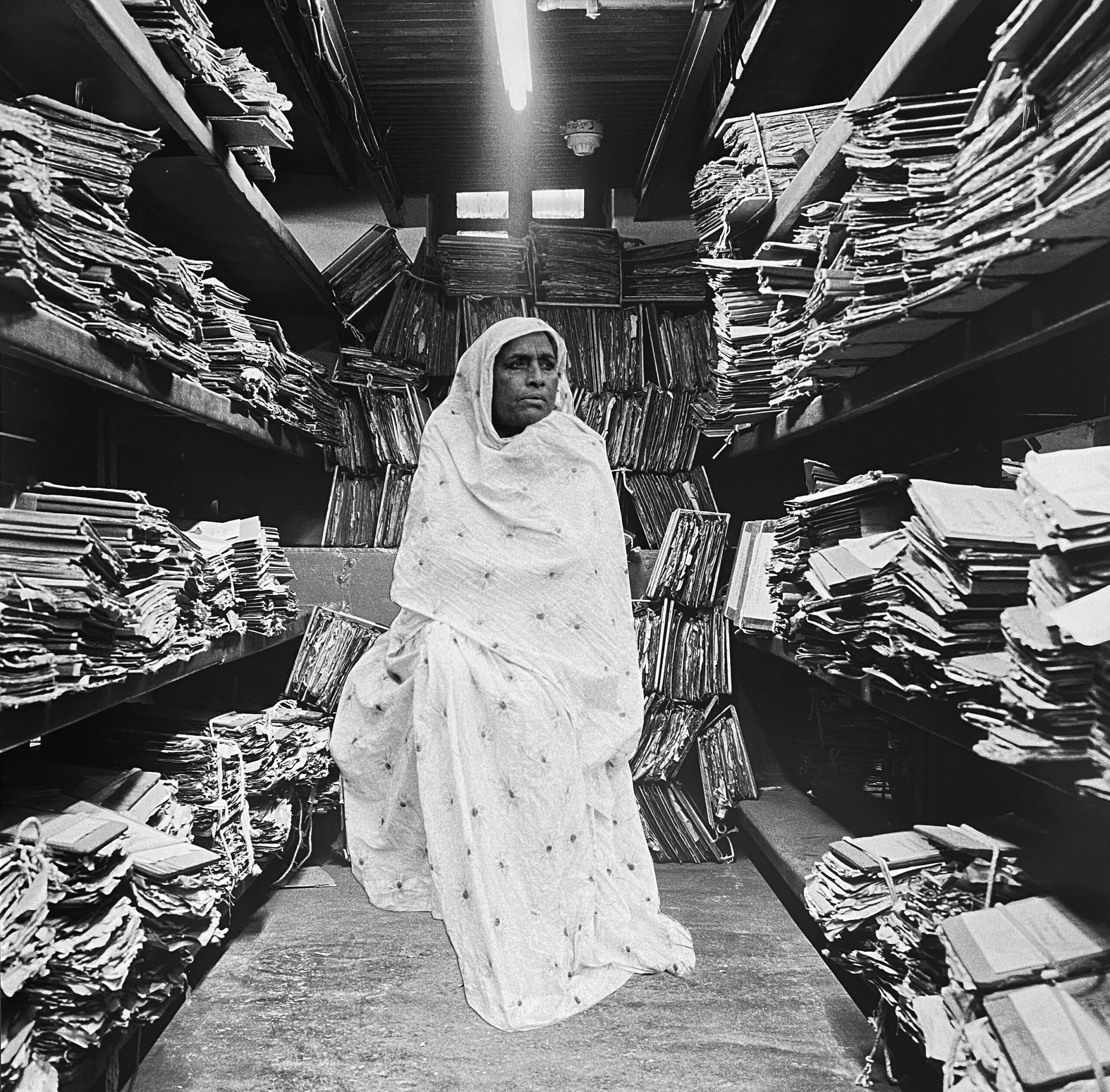

Dayanita Singh, Mona Montage, 2021 Photo: Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh, Mona Montage, 2021 Photo: Dayanita Singh

Your process is so deeply entwined with your own life. How can you be sure that viewers are able to respond to it?

Because if I am really true to myself, then somehow that comes through. If I’m trying to fake it, trying to appear very smart, then people see it immediately. When they come into the Mona room, they are going to feel the connection between Mona and me, and feel the loss that I feel, and they will know that this is honest work. The moment ego comes in, it’s finished and you need to start again.

Building exhibitions from your own books is a core aspect of your practice. Is the idea to make your work more accessible?

Everyone laughed when I said I wanted to turn a book into an exhibition, but at the Gropius Bau, that’s exactly what I’ve done. Look, rather than buying an expensive print of my work, you can buy one of my books for €60. Now the Gropius Bau is showing the exact same thing that you can have in your house. It starts an important conversation about value. That’s the real question the show will be putting to the audience. Maybe people won’t be interested in it, but from my perspective, it is asking: What makes something art? Just because it is a book, it is not art?

Are you undermining the whole gallery structure by making your work available in this way?

No, I think the gallery is important, and the publishing house is important, but I think both of those fields forget that there are also people like us in between – people who can’t afford to buy my colleagues’ works, but would love to have a little version of it. And I don’t want a little cup with their photo on it, I want something more, something where they have really engaged with the form. I think there is another kind of gallery that’s waiting to be made, a space that is in between the publishing house and the big fine art gallery.

Dayanita Singh, Museum of Chance, 2013. Photo: Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh, Museum of Chance, 2013. Photo: Dayanita Singh

This is the second mammoth show that you’ve put on with Stephanie Rosenthal, the Gropius Bau director. What’s been your experience of working with her?

There are very few curators who really love the artist, and want to help them realise their potential in a way that even the artist themselves doesn’t quite know. She is that kind of curator. Look what she’s done to the Gropius Bau – it used to be this dingy dark place, and look at it now.

Had you always wanted to work with photography?

It was the last thing I wanted to do as a child. But one night I realised that photography is my ticket to freedom, and that I could break my social obligations of being a good wife and having children. I started saying to people that I would love all of that but I am a photographer. People were so sweet and naive around me. They would say, “Poor thing, she can’t have children, she’s a photographer.” It served me well, as that is all I do – I just wanted to work, work, work.

Dayanita Singh: Dancing with my Camera Through Aug 7 Gropius Bau, Mitte

BIO

Born in New Delhi in 1961, Dayanita Singh studied at the International Center of Photography in New York City before taking up work as a photojournalist. Her first book, about the virtuoso tabla player Zakir Hussain, was published in 1986. Over her career she has created multiple “book-objects” that function as books, art objects, exhibitions and catalogues. In 2013 she presented her work at the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In 2022 she won the Hasselblad Award for photography.