WHAT EVERYONE SHOULD BE TALKING ABOUT THIS WEEK

As Oasis gear up for what could be the biggest reunion in British music history, are their implications for their return in a world that should have long moved on from late 20th century lad culture.

Words: Dan Harrison.

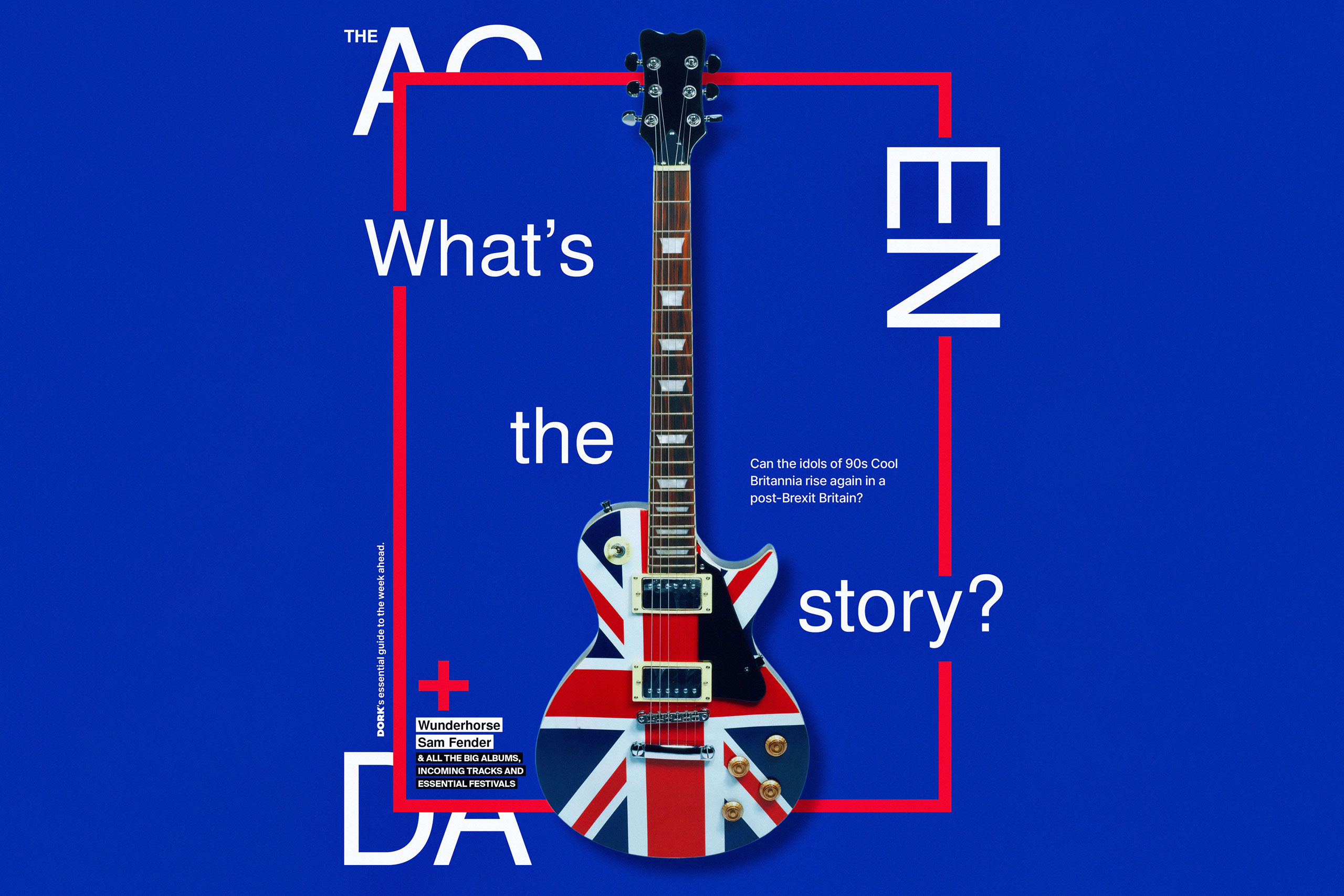

In the dimly lit back rooms of pubs from Manchester to Marylebone and back, the whispers grow louder. Twitter threads are spun and respun, tabloids prepare their headlines, and bucket hats — those ubiquitous symbols of 90s rebellion — are dusted off and worn with renewed pride. The band that defined a generation, the Gallagher brothers who divided a nation, might be on the brink of a comeback. Oasis, the embodiment of Britpop swagger, could be returning to the stage, and this time, according to whispers from some, it’s rumoured to be nothing short of monumental: perhaps a record-breaking 10-night residency at Wembley Stadium, maybe even followed by another ten in their hometown of Manchester. If it happens, it will be a cultural event of seismic proportions.

Oasis never did anything by halves. From their earliest days, they were a band who dared to dream big, to talk even bigger, and to back it all up with anthems that have since become woven into the fabric of British life. They famously claimed to be bigger than The Beatles, a statement that at the time was met with a mixture of derision and awe. But Oasis meant it, and their impact on British music and culture has been undeniable. Their potential return promises to be a defining moment for a country that has adopted their early albums as an unofficial national songbook. In a nation now navigating its post-Brexit identity, with a new Labour government promising change, it feels as though the ghost of Cool Britannia is being summoned once again, for better or worse.

The very idea of Oasis reuniting in 2024 feels almost paradoxical. They’re a band so deeply intertwined with a specific moment in time — the mid-90s, when lager flowed freely, and lad culture was king. But Oasis, as a band, have almost become detached from their songs, such is their omnipresence. Their anthems are sung in stadiums and pubs, at weddings and funerals. Liam and Noel may have long since parted ways, their personal and professional relationship shattered (and now perhaps mended) by years of feuding, but their music remains untarnished by the passage of time — or the cold hand of cancellation.

To grasp the significance of the moment, we must cast our minds back to 1994, when Oasis exploded onto the scene with ‘Definitely Maybe’. An era-defining album, it was a loud, brash rebuttal to the introspective grunge that had dominated the early 90s. Songs like ‘Live Forever’ and ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’ were declarations of intent from a working-class band that dared to do. The album’s success was meteoric, becoming the fastest-selling debut in UK history at the time. It captured the mood of a generation disillusioned with everything and yearning for something more hopeful, more optimistic. The raw energy and unpolished bravado of ‘Definitely Maybe’ set the stage for Oasis to become the latest big noise.

If ‘Definitely Maybe’ was the opening salvo, then ‘(What’s the Story) Morning Glory?’ was an atom bomb. Released in 1995, it catapulted Oasis from promising upstarts to global superstars. ‘Wonderwall’ and ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ transcended their Britpop origins to become cultural touchstones, anthems that are still sung with gusto in stadiums and karaoke bars alike. The album’s success was staggering, its impact seismic. Oasis seemed to reshape British culture in their image, their songs becoming the soundtrack to a nation’s collective consciousness.

Central to Oasis’ appeal was their unabashed working-class identity. In an industry often dominated by middle-class art school graduates, the Gallaghers’ council estate background and brash Mancunian accents cut through like a knife. They wore their class identity like a badge of honour, connecting with fans on a visceral level and positioning themselves as the authentic voice of a generation. Their identity wasn’t just a marketing tool; it was integral to their success, feeding the swaggering, gobby persona that would eventually contribute to their undoing.

But with great success came even greater excess, and 1997’s ‘Be Here Now’ was excess personified. The album’s release was a media event of unprecedented proportions. Dedicated programming on the BBC, radio shows dissecting every detail, and news stories about fans queuing up at the crack of dawn to get their hands on a copy all reflected the band’s dominance. The album’s success was instantaneous, almost predestined, but its bloated production and unrestrained track lengths soon came to symbolise not just Oasis at their most self-indulgent but Britpop’s overall decline. It was as if the entire movement had reached its zenith and begun to implode, all in the span of a single summer.

Throughout it all, Liam and Noel Gallagher became the swaggering, sneering faces of lad culture, a phenomenon that celebrated a particular brand of masculinity – brash, unapologetic, and often deeply problematic. In the 90s, their antics were seen as rebellious, even, to some, almost charming. Today, they invite more critical scrutiny. The Gallaghers’ behaviour — from Noel’s regular controversial comments to Liam’s alleged violence — casts a long shadow over their musical achievements. In an era of heightened awareness around issues of misogyny and toxic masculinity, the brand of laddish behaviour that Oasis embodied now feels uncomfortable, even indefensible.

Take, for instance, Noel Gallagher’s infamous wish that Alex James and Damon Albarn of Blur “catch AIDS and die”, a statement that was dismissed at the time as just another example of inter-band rivalry taken too far. Today, such a comment would rightly be condemned as hate speech. Similarly, Liam Gallagher’s alleged physical altercations, including accusations of domestic violence, have often been downplayed or ignored by a press more interested in the brothers’ latest quotable insults than in holding them accountable. More recently, Noel has made comments widely criticised as transphobic, demonstrating that these issues are not just relics of the past but ongoing concerns.

Yet, curiously, these controversies seem to have done little to dent the band’s popularity. Unlike other public figures who have faced backlash for similar transgressions, the Gallaghers’ star has remained largely undimmed. It raises uncomfortable questions about cultural attitudes towards violence and misogyny and about the double standards that allow certain figures to escape the consequences of their actions. It should force us to confront our own complicity in perpetuating harmful attitudes when we continue to celebrate artists who espouse them – the key word being should.

It’s a complex legacy that adds layers of tension and intrigue to the prospect of a reunion. It shouldn’t just be about whether Liam and Noel can share a stage again; it’s about whether they should occupy the same cultural space they once did in a world that has changed so dramatically.

The potential reunion also forces us to grapple with the thorny issue of nostalgia. Can Oasis recapture the magic that made them the biggest band in the world? More importantly, should they even try? The world has changed dramatically since Oasis’ heyday. The optimism of the 90s has given way to Brexit-era uncertainty. The attitudes and behaviours that were celebrated, or at least tolerated, in the band’s heyday, are now rightly scrutinised and often condemned.

On one hand, their music retains an undeniable power. Their classic songs are cultural artefacts, pieces of shared history that continue to resonate across generations. ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’, in particular, took on new meaning in the aftermath of the 2017 Manchester Arena bombing, becoming a hymn of resilience and unity in the face of tragedy.

On the other, the band’s problematic history and the Gallaghers’ ongoing controversial behaviour sit uneasily with contemporary values. For younger fans — those who know Oasis more by reputation than experience — the reunion offers a chance to see what all the fuss was about. But it also presents a potential clash of values. With the reduced platform their post-Oasis endeavours provided, many of their past transgressions have escaped the attention of the social media masses. As their status as Britain’s biggest band is restored, those misdeeds are less likely to escape the wrath of stanbases and a world that, quite simply, won’t put up with that kind of behaviour.

Liam Gallagher headlining Reading Festival over the August Bank Holiday weekend. (Photo credit: Patrick Gunning)

The solo careers of Liam and Noel since Oasis’ split in 2009 offer interesting insights into their individual artistic trajectories. Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds have seen him expand his sonic palette, incorporating elements of psychedelia and electronic music into his trademark songwriting style. He’s at least tried to evolve musically, even if commercial success has been more modest than his previous guise.

Liam, on the other hand, initially struggled to find his footing with Beady Eye, a band formed with other ex-Oasis members, but his solo career has seen a remarkable resurgence. Largely staying true to the classic Oasis sound, he’s benefited from a desire for nostalgia and an appetite for the band to return to active service, even if he’s not quite the vocalist he once was.

The influence of Oasis on contemporary artists is undeniable, even as the music landscape has shifted dramatically. There’s barely a British band that hasn’t been influenced by them – just by the osmosis of being born into a world in which they dominated. The brash confidence, the soaring choruses, the unapologetic ambition: these Oasis hallmarks can be traced through much of British rock music of the past two decades.

However, the way this influence manifests has evolved. While some bands have tried and largely failed to recreate the classic Oasis sound, others have taken the band’s spirit of ambition and applied it to very different musical styles. The 1975, for instance, channel Oasis’s grandeur and self-belief into a persona that incorporates everything from 80s pop to ambient electronica. While the swagger of Oasis is there, it’s filtered through a modern lens – and even then, it’s very much a case of for better or worse. The musical landscape today reflects a different kind of rock stardom, where social media presence and a more accessible, relatable persona often replace the gobby rock star image of the past.

Some accounts of the magnitude of the rumoured comeback cannot be overstated. If it was a ten-night residency at Wembley Stadium, the scale would be unprecedented, a flex of cultural muscle that few other acts could even contemplate. This is about making a statement that Oasis are not just back, but still capable of commanding the kind of reverence that only a handful of acts have ever achieved. It’s not really a shock that a couple of years after Blur play two Wembley shows, Oasis should return and add another eight on top. Such a move would be fittingly audacious, not to mention exceptionally profitable.

The scale of these rumoured shows is enough to make even the most jaded music fan’s heart skip a beat. Picture it: Wembley Stadium, packed to the rafters night after night, with 90,000 voices strong, all belting out every word. It’s the kind of communal experience that’s become increasingly rare in our fragmented cultural landscape. For those lucky enough to be there, it promises to be nothing short of euphoric – a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

And let’s not underestimate the emotional wallop of hearing these songs live again. There’s a reason why Oasis’s music has endured far beyond the band’s lifespan. They’re songs that form the soundtrack to a million memories, the backdrop to countless life-changing moments. It’ll be a visceral reminder of the power of music to unite, to uplift, and to transport us back to a time when anything seemed possible. For all the valid criticisms and the band’s complex legacy, there’s something undeniably magical about the prospect of Oasis reuniting. In a time of division and uncertainty, there’s a certain appeal to the idea of 90,000 people, arm in arm, singing their hearts out to ‘Live Forever’.

Yet the Oasis reunion, if it happens, won’t offer us neat resolutions or easy answers. It’s a messy affair that forces us to confront the contradictions in our cultural values. Can we reconcile our nostalgia with our progress, our love for the music with our distaste for its creators’ behaviour? Is it even possible to separate the art from the artist, especially when the music itself has grown to national treasure status? Are these songs, with their deep cultural resonance, even Oasis’ anymore, or have they been adopted by the public to the point where they exist beyond the band?

For all the complexities, there’s an undeniable thrill to the prospect of an Oasis reunion. These songs’ shared cultural heritage is unparalleled, save for perhaps one other band. As problematic as the Gallaghers may be, the strength of their early albums is undeniable. What’s certain is that these shows, should they happen, will be more than just another run of big stadium gigs. They will be an opportunity to revisit and reevaluate a moment in British history, to see if the music still resonates, and to confront the uncomfortable truths about the culture that birthed one of the biggest bands of all time.

The Oasis reunion could be a moment of reckoning – not just for the Gallaghers, but for everyone else too. It’s a chance to revisit old glories, confront old demons, and see if the past can truly be recaptured. And if nothing else, it will remind us why, for a brief, glorious moment, Oasis were the biggest band in the world. In doing so it might just force us all to ask some difficult questions about what we value in our cultural icons – and whether we’re prepared to accept the answers.

Leave a Reply