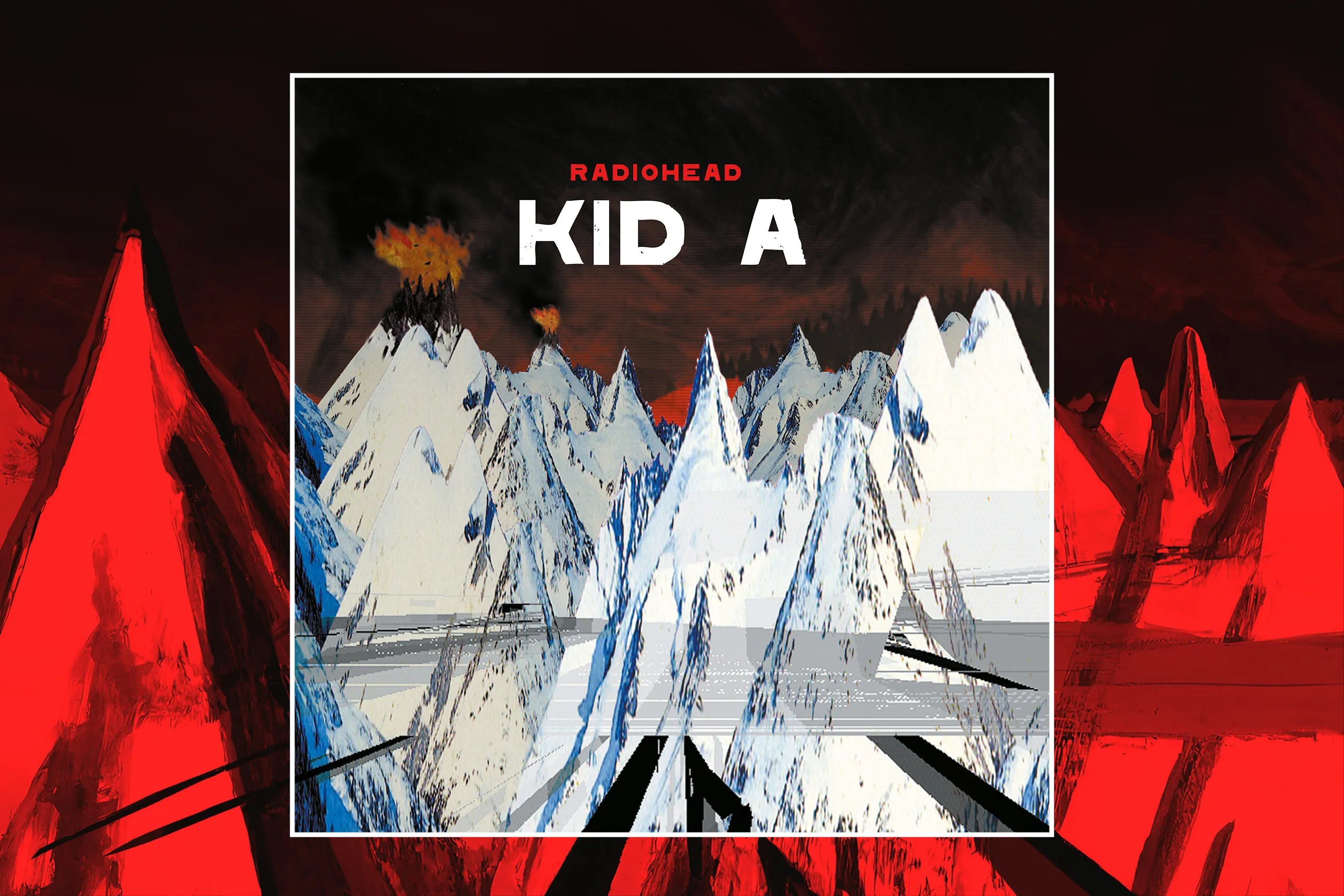

With ‘Kid A,’ Radiohead tossed aside their guitar anthems and conjured a futuristic soundscape beamed in from another dimension, creating an audacious, bewildering masterpiece that redefined modern music.

Words: Dan Harrison.

As the clock ticked over to the year 2000, while most were busy fretting about the Y2K bug and whether our toasters might suddenly develop a taste for world domination, five lads from Oxfordshire were quietly orchestrating a revolution. Radiohead, a band that had already redefined guitar rock with ‘OK Computer’, were about to pull off an even more audacious feat: they were going to make an album that sounded like nothing else on Earth.

‘Kid A’, released on 2nd October 2000, wasn’t so much a left turn as a teleportation to another musical dimension. Gone were the soaring guitar anthems and existential alt-rock that had made Radiohead the thinking person’s band of choice. In their place? A soundscape that seemed to have been beamed in from the future, or perhaps an alternate universe where synthesizers had evolved to develop feelings, and very complex ones at that.

To understand the seismic shift that ‘Kid A’ represented, we need to cast our minds back to the aftermath of ‘OK Computer’. That album, released in 1997, had captured the pre-millennial tension with such uncanny precision that you half expected each CD to come with its own portable bunker. It was a critical darling and a commercial triumph, the kind of success that usually sees a band either imploding spectacularly or churning out increasingly tepid versions of their big hit until even their most devoted fans start checking their watches at gigs.

Radiohead, being Radiohead, chose option C: total reinvention.

The gruelling ‘OK Computer’ tour left the band, particularly frontman Thom Yorke, feeling rather like they’d been put through a musical wringer. Yorke, it seemed, had developed a severe case of writer’s block, or perhaps more accurately, a severe case of not wanting to write anything that sounded remotely like what he’d written before. As he later told The Guardian, with all the cheer of a man describing his own root canal without anaesthetic: “When we finished the OK Computer tour, I had a sort of big… block. I basically thought that was it.”

Most bands faced with this conundrum might have resorted to some light plagiarism of their earlier work or perhaps a hastily arranged ‘back to basics’ album. Radiohead, ever the overachievers, decided instead to tear up the rulebook, feed the remains into a synthesiser, and then rebuild modern music from the ground up.

The result was an album that starts as it means to go on – by wrong-footing you entirely. ‘Everything in Its Right Place’ kicks things off with a synthesiser riff that sounds like it’s been composed by a particularly melancholic AI, while Yorke mutters cryptically about sucking lemons. It’s about as far from ‘Creep’ as you can get without actually leaving the solar system.

And that’s just for starters. ‘Kid A’ is an album that delights in confounding expectations at every turn. ‘The National Anthem’ sounds like a jazz band having a collective existential crisis, ‘Idioteque’ is a dance track for the apocalypse, and ‘Motion Picture Soundtrack’ closes proceedings with the kind of weepy, orchestral grandeur that wouldn’t sound out of place soundtracking the heat death of the universe.

Lyrically, Yorke seemed to have swapped his notebook for a Rorschach test, assembling phrases that ranged from the ominous (“We’re not scaremongering, this is really happening”) to the frankly baffling (“Yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon”). It was the kind of album that had critics reaching for their thesauruses and casual listeners reaching for the repeat button, determined to crack its code.

The reaction was, predictably, polarised. Some hailed it as a masterpiece, others dismissed it as pretentious noodling. More than a few Radiohead fans were left scratching their heads, wondering if this was some sort of elaborate prank. Had their heroes really swapped soaring guitar anthems for what sounded like a malfunctioning modem having an existential crisis?

But here’s the thing: ‘Kid A’ didn’t just survive the initial bewilderment, it thrived on it. It topped charts on both sides of the Atlantic, a feat that seems even more remarkable when you consider that the band promoted it with all the enthusiasm of a cat being forced to take a bath. No singles, no music videos – just some inscrutable ‘blips’ that looked like rejected idents for a particularly avant-garde cable channel.

As time went on, what initially seemed impenetrable began to reveal hidden depths. Listeners who stuck with it found themselves rewarded with new details, new connections, new reasons to furrow their brows in contemplation. It was the musical equivalent of a Magic Eye picture – stare at it long enough and suddenly you’re seeing things you never knew were there.

The influence of ‘Kid A’ on the musical landscape cannot be overstated. In its wake, a whole generation of indie bands suddenly discovered the joys of knob-twiddling and laptop noodling. Even mainstream pop felt the ripples, with everyone from Kanye West to Beyoncé citing it as an influence. It was as if Radiohead had given the entire music industry permission to get weird.

Two decades on, ‘Kid A’ has secured its place in the pantheon of great albums. It’s regularly topping ‘best of’ lists and being dissected in university music courses, presumably to the ongoing bafflement of students who were barely born when it was released. Its themes of alienation and technological anxiety seem more relevant than ever in our age of social media and artificial intelligence. It’s an album that’s aged like a fine wine, assuming that wine was made by a sentient computer and stored in a bunker designed by Stanley Kubrick.

But perhaps the true legacy of ‘Kid A’ lies not in its accolades or its influence, but in the way it challenges us to engage with music. In an age where songs are often treated as disposable background noise, it demands our full attention. It’s an album that reveals its secrets slowly, rewarding repeated listens and deep engagement. It reminds us that great art should sometimes be difficult, that it should challenge us, confuse us, maybe even frustrate us at first. But if we stick with it, if we give it the time and attention it deserves, it can change the way we see the world.

In the end, ‘Kid A’ stands as a testament to the power of artistic courage, a reminder that true innovation often means taking risks, challenging expectations, and being willing to alienate even your most devoted fans. It’s the sound of a band not just thinking outside the box, but building a new box entirely, then living in it.

‘Kid A’ is a journey, a puzzle, a revolution in sound. Two decades on, we’re still unravelling its mysteries, still discovering new layers of meaning. It remains a monolith, a challenge, and an inspiration. Not bad for a record that, on first listen, sounded like a malfunctioning robot having an existential crisis. Sometimes, it turns out, the artist really does know best.

Leave a Reply