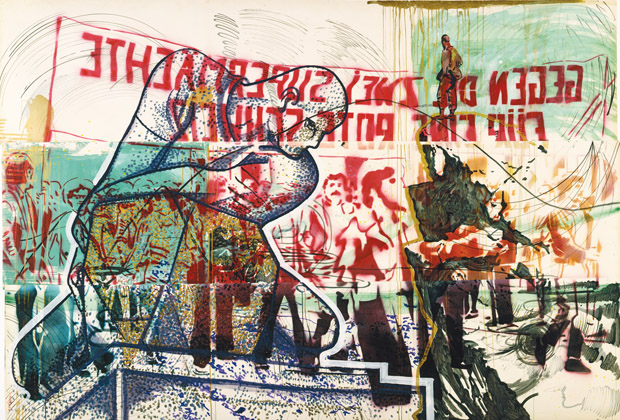

Photos courtesy of Bild KunstIn 1982 Klaus Staeck created a graphic print portrait of US president Ronald Reagan, the deep red background evoking the flames of hell with a south-facing atom bomb serving for the head. Today Staeck is president of the Akademie der Künste. His sleek glass-paneled office overlooks Pariser Platz; the US Embassy is his neighbor.

Photos courtesy of Bild KunstIn 1982 Klaus Staeck created a graphic print portrait of US president Ronald Reagan, the deep red background evoking the flames of hell with a south-facing atom bomb serving for the head. Today Staeck is president of the Akademie der Künste. His sleek glass-paneled office overlooks Pariser Platz; the US Embassy is his neighbor.

Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter

NEWSLETTER

Leave this field empty if you’re human: The irony of an anti-establishment graphic artist leading Germany’s art establishment is impossible to ignore. But an ironic worldview is essential to Staeck. It brought him close to Sigmar Polke, a founder of the Capitalist Realism movement and a man who loved to photocopy his own head.Polke died in June last year. The Akademie der Künste is now paying tribute to the German artist with an exhibition of 100 of his works, most of them graphic prints published by Staeck himself during their four-decade collaboration.Homage shows mostly works you published, as well as many personal artifacts that testify to your long and fruitful collaboration with Polke – it even includes faxes…Yes, among the personal items are 100 faxes partly altered by Polke in which I had asked him for an appointment. It is commonly known that Polke was very difficult to get a hold of. I met him only once in Heidelberg.When he saw a large copy machine in my gallery, he immediately put his head on the glass plate and later altered the copies further. He experimented a lot with photocopies. He came up with many patterns in this manner. In any case, to him the copies were never less relevant as art than paintings. This applied to Joseph Beuys too. The concept of a postcard was just as important to him as the concept of a large landscape. In that respect both artists were a lot alike.Polke was one of the founders of the Capitalist Realism painting movement. What was the goal of the movement?In my view, this was an early criticism of consumerist society during the Cold War. It was also the time of the so-called economic miracle. West Germans preferred to flee into consumerism and leisure activities. Capitalist Realism was an artistic political attack against this.Polke integrated everyday objects and trivial consumer articles into his imageworld. All of a sudden, sausages dominated a picture. Polke very consciously confronted the petty-bourgeois milieu and the eternal pedant. But one should know that Polke and his family fled the GDR, which elevated Socialist Realism to an artistic doctrine. Capitalist Realism was a critique of consumerist society and a response to the imposed Socialist Realism, but first and foremost a reaction to the developments in the West.

What can you tell me about the infamous ‘potato machine’?

The Potato Machine is the first multiple by Polke, which I published in 1969, our first common work. Initially, I only received a rough sketch. A technically talented friend in Heidelberg, a historian, somehow found a functioning motor and built 30 objects. The correct title is “Apparatus with which a potato can circle around another”.The potato machine also reminds me of the Dada movement: a considerable amount of effort just to let a potato circle around another one. The initial price was DM 330. Recently one was auctioned for €70,000.

I read about an instance where he only agreed to have an exhibition under the condition that the gallery owner would promise it would be the gallery’s last. Is that true?

I don’t know anything about that. But it’s possible. It is true that he had a very special humor. This was also something that linked us.

How did you come to know Polke?

Initially through a graphic arts exhibition, which I curated in 1967 for the Pratt Institute in New York and to which I invited Polke. Then, together with a friend, I organized the intermedia ‘69 which drew thousands of visitors to a student dormitory complex in Heidelberg. I contacted 12 artists to pledge support. Among them were Joseph Beuys, Dieter Roth, Christo, Klaus Rinke and Sigmar Polke, who contributed the potato machine. That’s when I met him in person for the first time.

What else should we know about Sigmar Polke?

To me he was the great mystery, reinventing himself again and again, participating in the events of the day fully awake, as few artists have, without the international fame going to his head. Polke never lived as publicly and was never as present in the media as Beuys, for example. There are basically no TV interviews with Polke. Beuys was a public preacher. Polke was not.

With Polke’s death, is there something missing from the art world?

With the death of an artist dies a part of a world of imagination. Nevertheless, just like any other human, each artist goes on living in the memories of the living. In the case of artists, this applies foremost to their oeuvre, which lives on just as well with Polke as with Beuys.HOMAGE TO SIGMAR POLKE | Jan 14-Mar 13